William Gilpin' rules of the picturesque, and my own Rear Ends of Sheep, Kherson

I've just been reading about William Gilpin's rules of the picturesque. In case you don't know him, he was an 18th C. curate/schoolteacher who came up with a set of rules to define what made a pretty picture, so that the aristocracy going on their Grand Tours of Italy and Scotland could be sure to make sure they could paint a work of genius that demonstrably conformed to the rules of what was good and what wasn't. I'm not sure what he has to say about sheep's backsides, but I hope he would have approved:

Kherson

Diary of a Lawyer in Moscow III - an ethical question, and the importance of cucumbers

Sometimes my lunch breaks as a lawyer at Linklaters were longer than they strictly should have been. I always carried a camera with a lens so sharp you could shave with it in my coat pocket or lawyerly briefcase. If the KGB ever followed me, they must have put me on their distinctly dodgy list, and wondered about the significance of the apparent innocuous scenes that I was clandestinely capturing. In this first picture, tucked away at the bottom of the frame, there is a figure sitting on a horse. He's the only statue in the scene - the workers erecting the scaffolding are real live people! The man on the horse is Zhukov. Not many people can claim to have saved western civilisation as we know it, but Zhukov can - or rather, could. He was responsible, probably more than any other person, for the defeat of Hitler. He rode a white horse that was famous for trotting in an odd way, with its feet on either side hitting the ground more or less simultaneously rather than alternately. Or so I heard.

The bronze of the statue had weathered to almost black. I was standing next to it when a babushka (little old lady) exclaimed to an accompanying child "The statue is all wrong, Zhukov's horse was white!" I turned to her and blurted out: "I believe Zhukov himself was white too".

Usually the witty riposte occurs to me five minutes later, five minutes too late, so I felt smug for at least a day after that. And in a foreign langauge too! In fact, still feel a bit smug, over a decade later.

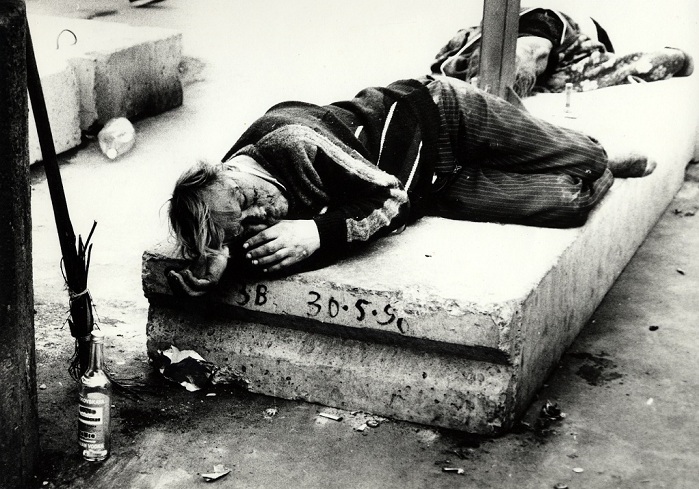

The second picture speaks for itself. I used to find it hard to look at, but then again, I don't see why I should, and now it no longer bothers me. But it is a disturbing image. Am I exploiting the woman in the picture? On the one hand, I'm giving her money, which can't be a bad thing, but maybe I'm only doing it to take her picture - would I have given her the money without taking the picture? So maybe it's exploitation. And I'm also taking her picture without her consent. The fact that I am wearing a jacket, apparently well dressed, doesn't help - and she is kissing my hand. There is something shocking about that. But why should there be? Is it shocking to wear a suit? Or to give money? Or to take someone's picture? Or to kiss someone else's hand? Or the combination of all these? Maybe the picture is uncomfortable because it puts in front of us something that we would rather not see? Who is at fault here: the photographer (me) for taking the picture, the owner of the hand (again me) for wearing a suit, the babushka for abasing herself, or the viewer for not liking to see some kind of truth?

I'm sure there's a PhD in there somewhere.

And the third picture - babushki s ogurchikami - for good luck. I find the smile and eyes of this babushka mesmerising, hundreds of years of babushkina bonhomie and supply of pickled cucumbers distilled into one look. It was taken at Novie Cheryomushki Market. Cheryomushki is a kind of cliche for a 'new' Soviet district in Moscow. Shostakovitch orchestrated a song about it which involves a chicken which doesn't want to be cooked which I sing from time to time in the bath.

And I think everyone understands the significance of cucumbers. No, not that significance, the other one: cucumbers = zakuska = bite on it to accompany a shot of = vodka. Cucumbers could be a kind of symbol of Russia in transformation, the engine that powers the drinking Russian muzhik from one end of the day to the other. A bit like potatoes for an Irishman, only with more vodka.

Diary of a Lawyer in Moscow II

In some ways these pictures reinforce a preconception about Russia. Harsh winters, alchoholism, poverty. Everything in shades of grey. It's Grim up North. Moscow has changed a lot, last time I was there, it looked more like Las Vegas with dazzling arrays of neon lights. It's easy to see where global warming is coming from - the lights around GUM Department Store themselves must surely have contributed 0.1 C or so to global temperatures. But in 1993 Moscow really did feel more black and white than now. Photographing in colour would probably not have made much difference. Everyone wore dark leather jackets or dark brown furs. Anyone wearing anything bright had to be a foreigner. There were few neon signs - most shops were still called things like "Meat No.9" or "Bread", and the only thing you could guarantee about their produce was that it would be meat or bread, and that it would be stale. Irish House on Arbat held Moscow's only western style bar, the Irish Bar, until Rosie O'Grady's opened a year or two later. The shop in Irish House was the only western style shop, and the only place in Moscow that sold milk that hadn't gone off. It was brought in fresh all the way from Ireland more or less daily. How it was made it through the notoriously slow and bureaucratic Russian Customs fast enough to keep fresh was a mystery - some Customs official somewhere must have become very rich.

In short, to a foreigner, who always had the option of leaving the place when it got too much (which it did frequently), Russia felt exotic and romantic, a living and breathing Le Carre novel, where anything might happen, and often did.

I rented my first flat at Taganka, opposite the avant garde theatre which had constantly been at odds with the Soviet authorities, where Vysotsky had been a lead actor. Vysotsky was a kind of Soviet superstar singing poet - something like the Beatles rolled up into Louis Armstrong (his voice had something in common) rolled up into T.S. Eliot. When he died and was laid out at the Taganka theatre, the Soviet authorities tried to keep news of his funeral quiet, but tens of thousands of people turned out to attend - so many that the attendance at the Olympic events that were in full swing dropped noticeably that day.

After I had been at Taganka a year or so, there was a general renovation of the appartment building, which involved taking out the pipework, and rats began to run around in the flat using the holes left by the pipework, one of them strolling casually through the kitchen during tea and another waking me up by running across my bed at night. I moved from there shortly after, not so much driven away by the rats as by a lunatic landlord who insisted on visiting regularly using his own key.